This Saturday September 7, we’re exploring the legacy of the Chinese architects who built Shanghai. One of their major contributions was a new riff on Art Deco architecture: Chinese Art Deco. What was Chinese Art Deco, and how did it come about? Here’s the story. To book the walk, click here.

Art Deco-era Shanghai, between the 1920s-1940s, was the very essence of a global city: Foreigners in suits shared the streets with locals in changpao; you could get around via rickshaw or tram, and the imposing European buildings of the Bund faced Chinese junks and fishermen in the Huangpu River.

The Shanghainese embraced this East-meets-West aesthetic in design, fashion and in Art Deco architecture. Art Deco may have originated in Europe, but it was born during a moment of colonial expansion, travel, and cross-cultural influence, becoming a global phenomenon. Artists, writers, and intellectuals traveled the world, and so did Art Deco, often taking on the characteristics of the places where it landed – in Shanghai’s case, it was elements from traditional Chinese architecture and art that sinified its Art Deco.

Liu Jipiao and the Birth of Chinese Art Deco

But even before Art Deco arrived in Shanghai*, Chinese Art Deco design was exhibited in Paris. In 1925, the International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts gathered a groundbreaking display of modern decorative arts in Paris that established the Art Deco style. It was emblematic of the times that the United States declined to participate because, they said, there was no modern design in America, but China was represented, with a striking Chinese Art Deco section designed by the artist and architect Liu Jipiao (刘既漂).

*Art Deco landed in 1926, in the ballroom of the Cercle Sportif Français.

China in 1925 was a relatively new republic, and younger citizens like Liu, then a student at L’Ecole Nationale des Beaux Arts, were eager to modernize and strengthen their country. People of Liu’s generation grew up in a relatively cosmopolitan China, one that was open to trade and international influences following its defeat in the 19th century Opium Wars. Yet China was also humiliated by this loss at the hands of foreigners, which led many young Chinese to explore modernizations that were not synonymous with westernization – modernization with Chinese characteristics.

There are only a few images of Liu’s Chinese pavilion, but those that exist show this dream of a Chinese modernization in visual form: traditional motifs of classical Chinese imagery – clouds and three-toed scaly dragons – are streamlined and modernized. Liu designed the cover of the catalogue as well, also featuring classical Chinese imagery in a dramatic modern style, and what may be the first modernizations of Chinese characters to match this new style. It was an early melding of Chinese elements with Art Deco, a uniquely Chinese style that was later embraced by a generation of Chinese architects and artists.

The First-Generation Chinese Architects

Foreign architects originally dominated the field of architecture in Shanghai, but by the 1920s, this began to change as increasing numbers of Chinese students studied architecture abroad – in the U.K., Germany, France, and the U.S. A significant cohort studied at the University of Pennsylvania under Paul Philippe Cret; some 22 Chinese students were enrolled at U Penn in the two decades starting in 1918.

These young architects were talented, and could design in any style the client wanted, from neoclassical to Bauhaus. But foreign clients wouldn’t hire them, so their commissions came from Chinese clients and the Nationalist government. As they explored what it meant to be Chinese and modern, they developed Chinese Deco: buildings featuring Art Deco’s geometric lines and design elements, often in the form of Art Deco skyscrapers, with modernized Chinese elements such as Chinese roofs, traditional patterns, and Chinese characters.

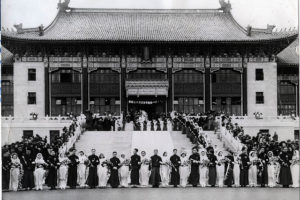

Notably, several of the Chinese architects who pioneered Chinese Art Deco had worked with American architect Henry K. Murphy. Murphy, who first came to China in 1914, was so impressed with traditional Chinese architecture that he incorporated its elements into his designs for university campuses (including Shanghai College, Ginling College, and Nanjing University) – the first examples of the East-West mix that would evolve into Chinese Deco.

Who were these first-generation architects, and what did they create? Some highlights:

DONG DAYOU

There was Dong Dayou, a University of Minnesota graduate, who designed the Greater Shanghai Plan buildings in Jiangwan. This collection of modernist buildings with Chinese characteristics was intended to be Shanghai’s new civic center, but war interrupted those plans. Several of the buildings have been refreshed, and they are Shanghai’s most dramatic collection of Chinese Deco architecture.

POY GUM LEE

American-born Poy Gum Lee trained in New York at the Pratt Institute and Columbia University before moving to Shanghai in 1923. Hired by the YMCA Building Bureau for China, he designed 12 YMCAs in China before starting his own practice in 1927. In Shanghai, Lee is known for two Chinese Deco buildings: the National YWCA and the Chinese YMCA (1931), the latter designed with U Penn graduates Robert Fan and Zhao Shen. When Lee returned to New York, he continued to design Chinese Deco buildings, which can still be seen in Chinatown.

ROBERT FAN

Robert Fan Wenzhao trained at U Penn, then returned to his hometown of Shanghai to design some of the city’s most impressive buildings, including the Nanking Theater, the Majestic Theater, the Georgia Apartments, and Yafa Court.

Fan’s Chinese YMCA, designed with Poy Gum Lee and Zhao Shen, is a masterpiece of Chinese Deco, combining typical elements of Chinese architecture (the scaled down Chinese roof, for example) with Moderne lines. The YMCA’s interior features classic imperial palace design on the ceilings, doors, even the staircase, highlighting the geometry in the traditional design.

KWAN, CHU & YANG: Kwan Sung Sing, Chu Pin, and Yang Tingbao

There are only a few examples of the work of Tianjin-based architectural firm Kwan, Chu & Yang in Shanghai, but they are spectacular.

The three principals were graduates of U.S. universities: Kwan Sung Sing was the first Chinese graduate of MIT’s architecture program, while Chu Pin and Yang Tingbao studied at the University of Pennsylvania. Kwan, Chu & Yang designed Sun Department store, which dominates the corner of Nanjing Road and Tibet (Xizang) Road, a curved beauty with delicate Chinese filigree details.

Not far away stands their Young Brothers Bank, which, sadly, was never fully completed. So while there are Chinese elements on the façade, the planned Chinese roof was never executed.

LUKE HIM SAU

One of the city’s most iconic Chinese Deco buildings is Luke Him Sau’s (Lu Qianshou) Bank of China headquarters on the Bund – the only Chinese-style building on the famous street. One of the first Chinese architects to be trained at the Architectural Association in London, Luke’s Bank of China is an excellent example of how Chinese Deco modifies traditional Chinese architecture: The Chinese roof with its extensive, sweeping eaves is simplified into a smaller, more streamlined version. The building’s Chinese lattice pattern is reminiscent of classic Art Deco speedlines, racing down the front of the building. Interestingly, Luke’s original design was purely modernist with no Chinese elements – those were added at the insistence of the Nationalist government.

INTERIORS

It wasn’t just the exteriors: interiors, too, received the Chinese Deco treatment, from stylized characters to traditional patterns gone Moderne.

Some of Shanghai’s best interior Chinese Deco includes the Fairmont Peace Hotel’s Dragon & Phoenix Room, the National YWCA, the Greater Shanghai Plan Mayor’s Building and Library in Jiangwan, the Chinese YMCA, and the (secret) Continental Bank lounge.

Chinese Deco does not seem, at first glance, to have many standard elements of traditional Art Deco – porthole windows, speedlines, pastel colors, etc. What makes it Art Deco, however, is not the ornamentation but the form. And if you look closely, you might even see some portholes…

We leave you with some thoughts from Robert Fan that should apply to all buildings: “Beauty and character are built into a wall, not applied after it is completed.”

Most Commented Posts